As Russian soldiers marched into Ukraine, the question on everyone’s mind was: “What does Putin hope to achieve with such a massive invasion?” Of the many fanciful distortions manufactured as justification, the pressing need for Ukraine’s “de-Nazification” is the most ludicrous.

In making his case for entering Ukrainian territory with armoured tanks and fighter jets, Russian President Vladimir Putin declared the “special military operation” was undertaken “to protect” victims of the Kyiv regime’s “genocide,” and that Russia “will strive for the demilitarisation and de-Nazification of Ukraine.”

On its face, Putin’s slander is farcical, not least because Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is Jewish, and members of his family were killed during World War II. There is also no proof of mass killings or ethnic purges undertaken by the Ukrainian government. Marking adversaries as Nazis is a typical political tactic in Russia, particularly as leaders benefit from disinformation crusades.

Implying Ukraine is strongly allied with Nazism has been a regular feature of Russian media coverage. The Russian Foreign Ministry posted on Twitter that Ukraine and America voted against a Russian-endorsed UN resolution that would condemn the veneration of Nazism. This neglects to clarify that both countries declined to support Russia’s resolution because they believed it was advancing Moscow’s propaganda objectives, with the U.S. claiming it was a “thinly veiled attempt to legitimise Russian disinformation campaigns.”

Despite a long history of anti-Semitism and pogroms, on the eve of World War II, Ukraine was home to one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe. When German soldiers took control of Kyiv in 1941, they were greeted with “Heil Hitler” banners. Not long after, nearly 34,000 Jews were assembled and trudged to fields outside the city to be slaughtered in what became known as the “Holocaust by Bullets.” Following World War II, because of the policy of state anti-Semitism, all Jewish organisations and institutions were shut down across the Soviet Union from the late 1940’s until its dissolution.

Nowadays, Ukraine’s Jewish community can rejoice in liberties and protections unconceived of by previous generations, including a recent law criminalising anti-Semitic actions. But this law was not introduced without reason — it was designed to tackle a marked increase in public demonstrations of intolerance, specifically Swastika-littered defacement of synagogues and Jewish monuments, and unnerving demonstrations that saluted the Waffen SS. In another unfavourable development, in recent years the country has put up a plethora of monuments venerating Ukrainian nationalists whose legacies are polluted by their undeniable history as Nazi proxies.

The idea that Ukraine is in desperate need of “de-Nazification” is a well-established Russian nationalist narrative. It emanates from World War II, when some Ukrainian partisans aligned with the Nazis against the Soviet Union. Today, Putin has interlaced this history into his fundamentalist visualisation that Ukraine is not a legitimate sovereign country. For Putin, Ukraine is not simply a historically Russian territory incorrectly detached from the motherland. Rather, Ukraine is the successor of a neo-Nazi practice that perpetrated atrocity in Russian in World War II.

Putin’s accusations of genocide also reflect this nationalist narrative. Ukraine includes large ethnic Russian populations, particularly in the east, and many Ukrainians of all ethnicities speak Russian. Putin depicts these people as not simply rightful Russian citizens unjustifiably partitioned from the motherland, but as possible casualties of an ethnic cleansing crusade by the so-called Nazi Ukrainian government.

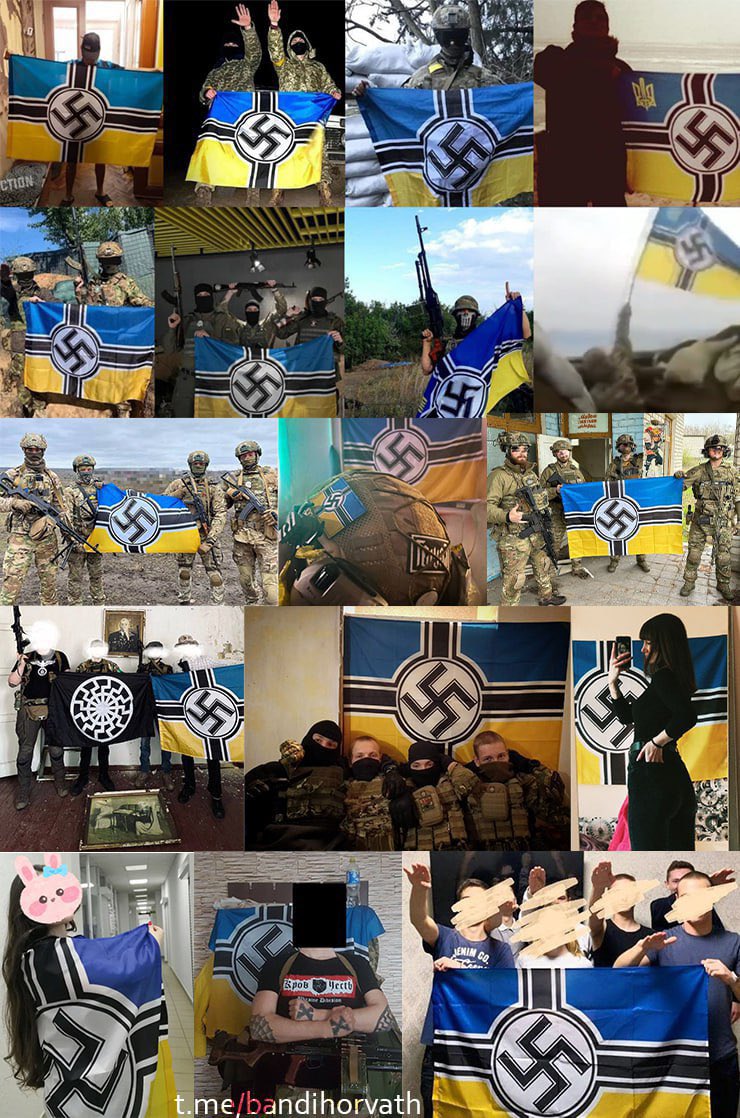

This is not to deny the far-right threat in Ukraine. Ukraine has a genuine Nazi problem. The most noteworthy, the Azov Movement, is a militia that was instrumental in countering Russia’s incursion in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Initially established as a volunteer group in May 2014, the Azov Battalion developed from the ultra-nationalist Patriot of Ukraine gang and the Social National Assembly. Its inaugural commander was white nationalist Andriy Biletsky ‒ dubbed White Ruler by his supporters ‒ who infamously declared in 2010 that Ukraine’s national purpose was to “lead the white races of the world in a final crusade … against Semite-led Untermenschen [i.e., inferior races].”

Azov gained a reputation with the 2014 Battle of Mariupol, when the Battalion recaptured the eastern Ukrainian city from pro-Russian separatists, establishing its reputation as fierce defenders of Ukraine, willing to fight back against severe odds. Its integration into the Ukrainian National Guard has afforded it a degree of impunity, and made Azov the crème de la crème of its international far-right, neo-Nazi peers. Since, Azov has exploited Ukraine’s predicament to make itself appear more conventionally mainstream by providing public civil defence training gatherings.

Although Azov denies it adheres to Nazi ideology as a whole, its uniforms continue to bear Nazi symbols including SS regalia and the neo-Nazi Wolfsangel symbol, used by Nazi units during World War II. Since 2014, Azov has actively fomented international links, courting support from global far-right, neo-Nazi networks, and outside Ukraine, Azov have seized a principal role in a network of extremist groups that extend from the U.S., Europe, and New Zealand.

Putin has seized upon far-right currents within Ukraine’s militias as evidence of reactionary Nazism while simultaneously cultivating far-right, ultranationalist sentiments. Russia’s most infamous military proxy, the Wagner Group, operates in support of Russian foreign policy objectives, and is trained on installations of the Russian Ministry of Defence. Moscow has utilised their expeditionary forces to wage deniable war and promote the Kremlin’s interests in places like Libya, Syria, Mozambique, and Mali.

The Wagner Group is named after 19th century German composer Richard Wagner, whose music Adolf Hitler adored. In a photo that first emerged on Russian VK accounts and a Telegram group associated with the mercenaries, the group’s leader, Dmitry Utkin, dons neo-Nazi tattoos, including a swastika, Waffen SS lightning bolts, and a Reichsadler Eagle. Wagner mercenaries have reportedly left behind neo-Nazi propaganda in the conflict zones they have meddled in. In Libya, pictures appeared of Wagner combatants, some garbed in German World War II uniforms, purportedly re-enacting scenes from Rommel’s operation against British troops in Libya in 1942.

The Wagner Group been heavily involved in Russia’s protracted war on Ukraine. Its units aided Putin’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014 and rebelled alongside pro-Russia separatists in eastern Ukraine. They have also been operating in the present conflict, with dozens of Wagner mercenaries pulled from the Central African Republic to join Russian forces amassing in Ukraine.

There is also the neo-Nazi, white supremacist group the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), which the U.S. State Department designated a terrorist organisation in 2020. With the Kremlin’s implicit authorisation, the RIM operates paramilitary camps near St. Petersburg, in which neo-Nazis and white supremacists from across Europe are instructed in terrorist tactics.

Putin also utilises neo-Nazi organisations beyond warfare operations. An essential element of the Kremlin’s crusade to manipulate cracks in the West is exploiting transnational white supremacist movements to endorse racially and ethnically inspired violent extremism. Russia serves as a sanctuary and networking hub for far-right extremists, with one of America’s most infamous neo-Nazis finding refuge there. Rinaldo Nazzaro, leader of The Base, an American neo-Nazi, white supremacist paramilitary organisation, lives in Russia and guides the group from St. Petersburg.

Among the virtual ecosystems populated by far-right, white supremacist extremists, Russia’s wanton invasion of Ukraine has been a considerable focus of conversation. Opinion is split — the far-right, white supremacist online environment has never been a monolith. While some ally with Putin, others support Ukraine, or simply hope for carnage and mayhem. Putin’s mission has found a receptive audience among far-right extremists in America, who often look to Putin’s Russia as the last bastion of white, Christian purity. Moscow and its proxies have provided finance and other assistance to these far-right populists across Europe and North America since long before Russia’s invasion. Even before the invasion, as tensions increased between Russia and Ukraine, some far-right groups were already disseminating pro-Russian, anti-Western, anti-Semitic propaganda.

Putin’s weaponisation of neo-Nazis was always a dicey tactic, but it was not illogical. Unlike mainstream nationalists, who often support the concept of free elections, neo-Nazis repudiate democratic institutions and the very idea of egalitarianism. For a dictator disassembling democracy and engineering an authoritarian regime, they were perfect accessories. In Ukraine, Putin is not combating neo-Nazism. The country most in need of “de-Nazification” is Putin’s Russia.

This article was one of the top ten most read articles published in 2022.

Fiona Ballentine is a student at the Australian National University, studying a Bachelor of International Relations and a Bachelor of Arts, with a major in Middle Eastern and Central Asian Studies. Fiona was an intern at the AIIA National Office from February-April 2022.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be re-published with attribution.

Putin's claim of fighting against Ukraine 'neo-Nazis' distorts history, scholars say Updated March 1, 20223:02 PM ET By

Rachel Treisman

Russian President Vladimir Putin invoked World War II to justify Russia's invasion of Ukraine, saying in televised remarks last week that his offensive aimed to "denazify" the country — whose democratically elected president is Jewish, and lost relatives in the Holocaust.

"The purpose of this operation is to protect people who for eight years now have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kyiv regime," he said, according to an English translation from the Russian Mission in Geneva. "To this end, we will seek to demilitarize and denazify Ukraine, as well as bring to trial those who perpetrated numerous bloody crimes against civilians, including against citizens of the Russian Federation."

Russian officials have continued to employ that rhetoric in recent days.

Russia's Foreign Ministry last week accused Western countries of ignoring what it called war crimes in Ukraine, saying their silence "encouraged the onset of neo-Nazism and Russophobia." Russia's envoy to the United Nations reiterated over the weekend that it is carrying out "a special military operation against nationalists to protect the people of Donbass, ensure denazification and demilitarisation."

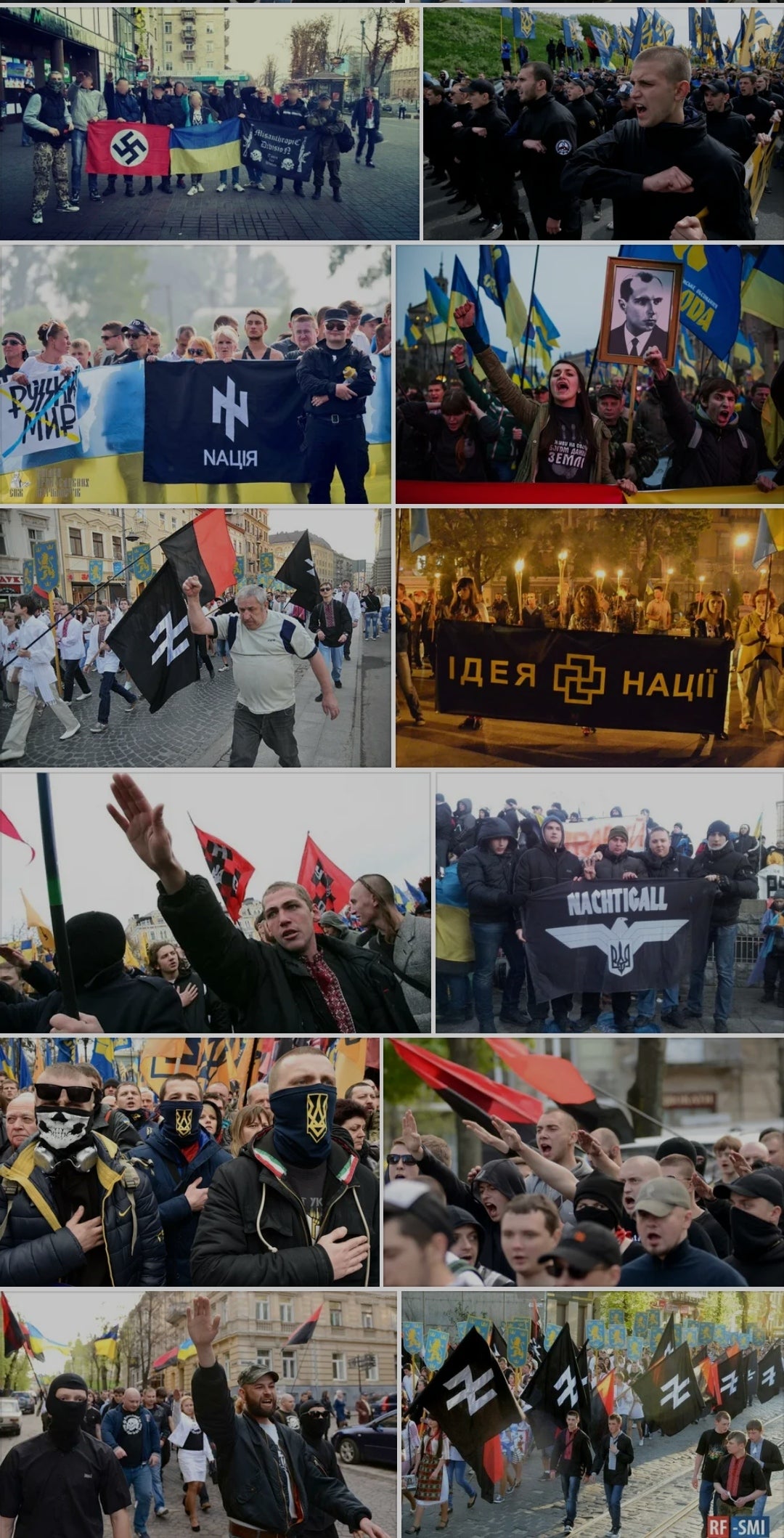

And Putin has accused "Banderites and neo-Nazis" of putting up heavy weapons and using human shields in Ukrainian cities. Banderites is a term used — often pejoratively — to describe followers of controversial Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera, and Ukrainian nationalists in general.

The Russian invasion, and the language of "denazification" as a perceived pretext for it, quickly drew backlash from many world leaders, onlookers and experts alike.

Criticisms of Russia's perceived hypocrisy grew even louder on Tuesday, when Russian strikes hit a memorial to Babyn Yar — the site where Nazis killed tens of thousands of Jews during World War II.

Ukraine's official Twitter account posted a cartoon of Putin and Adolf Hitler gazing lovingly into each others' eyes, writing that "This is not a 'meme,' but our and your reality right now." The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, among others, said Putin "misrepresented and misappropriated Holocaust history."

A lengthy list of historians signed a letter condemning the Russian government's "cynical abuse of the term genocide, the memory of World War II and the Holocaust, and the equation of the Ukrainian state with the Nazi regime to justify its unprovoked aggression."

They pointed to a broader pattern of Russian propaganda frequently painting Ukraine's elected leaders as "Nazis and fascists oppressing the local ethnic Russian population, which it claims needs to be liberated."

And while Ukraine has right-wing extremists, they add, that does not justify Russia's aggression and mischaracterization.

Putin's language is offensive and factually wrong, several experts explain to NPR.

It's a harmful distortion and dilution of history, they say, even though many people appear not to be buying it this time around.

Laura Jockusch, a professor of Holocaust studies at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, told NPR over email that Putin's claims about the Ukrainian army allegedly perpetrating a genocide against Russians in the Donbas region are completely unfounded, but politically useful to him.

"Putin has been repeating this 'genocide' myth for several years and nobody in the West seems to have listened until now," she says. "There is no 'genocide,' not even an 'ethnic cleansing' perpetrated by the Ukraine against ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers in the Ukraine. It is a fiction that is used by Putin to justify his war of aggression on the Ukraine."

She adds that his use of the word "denazification" is also "a reminder that the term 'Nazi' has become a generic term for 'absolute evil' that is completely disconnected from its original historical meaning and context."

The baseless claims are part of a broader pattern The scholars characterize Putin's claims about genocide and Nazism as part of a long-running attempt to delegitimize Ukraine.

The Soviet Union used similar language — like calling pro-Western Ukrainians "Banderites" — to discredit Ukrainian nationalism as Nazism, explains José Casanova, a professor emeritus of sociology at Georgetown University and senior fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

"And now we see [Russia is] doing it every time the Ukrainians try to establish a democratic society, they try to say that those are Nazis," he says. "You need to dehumanize the other before you are going to murder them, and this is what's happening now."

Olga Lautman, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis and co-host of the Kremlin File podcast, says Russia amped up the Nazi narrative after seizing Crimea from Ukraine in 2014.

Ukraine is home to ultranationalist movements, including most prominently the Azov Battalion, which formed in 2014 and later joined the country's National Guard after fighting against Russian-backed forces in eastern Ukraine.

But Lautman estimates nationalists make up about 2% of Ukraine's population, with the vast majority having very little interest in anything to do with them.

She said the U.S. probably has a higher percentage of white supremacist and Nazi groups, while Casanova also says Ukraine has a smaller contingency of right-wing groups than other Western countries.

They also note that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is Jewish, as is the former prime minister, Volodymyr Groysman.

Zelenskyy was elected in 2019 with a whopping 73% of the vote — a considerably larger share than his predecessors — and won a majority in every region, including the most traditional and conservative, according to Casanova.

"In no other European country could you have ... a president, a prime minister being Jewish without having a lot of antimseitic propaganda in media and in newspapers," he says. "It never became an issue."

The Holocaust took a personal toll on Zelenskyy's family. Three of his grandfather's brothers were killed by the Germans, he said in a January 2020 speech.

"He survived World War II contributing to the victory over Nazism and hateful ideology," he said of his grandfather. "Two years after the war, his son was born. And his grandson was born 31 years after. Forty years later, his grandson became president."

Experts and observers criticize Putin's "mythical use of history" Putin's claims contradict and distort important parts of 20th-century history while furthering his own agenda, the experts tell NPR.

They characterize it as an effort to hark back to the Soviet Union's heroism in fighting fascism during WWII.

But Casanova notes that Ukraine "suffered more than Russia from Nazi tanks," saying it lost more of its population during the war than any other country (without counting Europe's 6 million Jewish victims as a nation).

He calls Putin's tactics "simply a mythical use of history" to justify present-day crimes.

It's true that many Ukrainian nationalists initially welcomed the German invaders as liberators during WWII and collaborated with the occupation, a fact that Ukraine's small far-right movement is quick to emphasize. Putin's claims seize on that kernel of truth but distort it — a classic Soviet propaganda tactic.

Lautman, who is Ukrainian and Russian, says Russia considers WWII its biggest victory and places a big emphasis on its defeat of the Nazis, celebrating WWII Soviet holidays many times a year.

Russian television channels played WWII movies on the day of Putin's announcement about invading Ukraine, Lautman says, which she describes as an appeal to the older generation.

And Russian leaders have successfully rewritten parts of that history, she says. For example, Putin signed a ban on comparisons between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany last July. That means someone could be jailed for mentioning the collaboration between Hitler and Josef Stalin, Lautman explains.

Jockusch notes another gap in Russia's retelling of its 20th-century history. "Stalin perpetrated a man-made famine that can be called a genocide in Ukraine 90 years ago, the 'Holodomor' which Russia still does not recognize and which claimed some 3 million Ukrainian lives," she says.

So why would Putin use this particular language to justify an invasion now?

Lautman says Putin has long mourned the collapse of the Soviet Union and has "nothing to show" despite having been in power for two decades.

"If he's able to reclaim some of this lost territory, on top of having a few satellite states, which he's been attempting to do over the past decade ... then at least he would have a legacy to leave in the history books of Vladimir the Great," she says.

What this distortion of history can teach us While the West may not have been paying close attention before, many critics in Europe and beyond are now pushing back on Putin's claims.

Lautman says Ukrainians are used to this kind of language, since it's consistent with what Russia has been putting into the information sphere over the last eight years. And despite strict media censorship in Russia — where outlets aren't even allowed to refer to the current incursion as a war — citizens are risking imprisonment by protesting in the streets.

Yale historian Timothy Snyder described the charge of denazification as a perversion of values, telling CNN that it is "meant to confound us and discourage us and confuse us, but the basic reality is that Putin has everything turned around."

He said Putin's goal appears to be to take Kyiv, arrest Ukraine's political and civil leaders to get them out of power and then try them in some way. That's where the language of genocide comes in, he added.

"I think it's very likely, and he's said as much, that he intends to use the genocide and denazification language to set up some kind of kangaroo court which would serve the purpose of condemning these people to death or ... prison or incarceration."

Casanova and Lautman praise the strength and determination of Ukrainians, noting they are putting up a resistance. If Russia does succeed, Lautman says she is confident it would round up and execute political leaders and journalists there.

The experts point to the importance of learning from history and the present moment, something that the U.S. and other countries have not always done.

Casanova says the current moment proves that the world must create an equitable security system that is "not manipulated by the superpowers."

And both he and Lautman call for the world to hold Russia accountable, including by trying it for war crimes in international court. (The top prosecutor at the International Criminal Court said on Monday that the body would open a formal investigation into alleged war crimes "as rapidly as possible.")

"[We have to] understand that Ukraine today is the sacrificial lamb for all the unwillingness of the West to act united in defense of its own norms and values, in defense of the world security system that they tried to establish," Casanova says. "And if they can't fight for that, I don't know for what they can fight."

Russian soldiers deliberately kill Ukrainian kids, new film says Terror against civilians is part of Russian military strategy, experts say.

KYIV — Russia’s army has killed more than 500 children in Ukraine since the start of its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukrainian prosecutors say.

In the new documentary “Bullet holes,” journalists from the Kyiv Independent — a Ukrainian English-language news website — tell stories of three children killed by Russian troops in Ukraine: 10-year-old Kateryna Vinarska; 12-year-old Vladyslav Mahdyk; and 15-year-old Mykhailo Ustianivsky.

All three were shot dead by Russians at close range, according to Kyiv Independent reporters.

Vinarska was killed by Russian soldiers as they shot at a civilian car belonging to her grandparents at a checkpoint in an occupied village in the Kharkiv region. Mahdyk was shot dead by a single Russian bullet that also wounded his older sister as the family was trying to evacuate from Russian-occupied territory in the Kyiv region. And Ustianivsky was shot in the back for running away from a Russian armored vehicle in his village in the Kherson region, also occupied by Russian forces.

Their killers remain unpunished, and the children’s families are devastated — and want justice.

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Center for Civil Liberties — a Ukrainian watchdog documenting Russian war crimes — who is also featured in the film, said that Russia is deliberately using terror against civilians to break Ukraine’s resistance.

“These crimes are committed in all regions and they continue. We are ready to prove it in court. Because it is time to break the circle of impunity and cruelty that has become part of Russian culture,” Matviichuk told the Kyiv Independent in the film.

As of September, 504 children had been killed in Ukraine as a result of Russian aggression, Ukrainian prosecutors say.

Russia has repeatedly denied committing war crimes in Ukraine and even blamed Kyiv for killing its own people, claiming it only invaded Ukraine to prevent genocide.

Ukrainian officials have long fumed at Moscow’s accusations.

“Can a state use false allegations of genocide as a pretext to destroy cities, bomb civilians, and deport children from their homes? When the Genocide Convention is so cynically abused, is this court powerless? The answer to these questions must be no,” said Ukraine’s representative Anton Korynevych, during the recent World Court hearings in The Hague, where Kyiv has sued Moscow for abusing the Genocide Convention.

In turn, Kyiv says that Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine show signs of genocide. But the U.N. Commission of Inquiry has not yet found enough evidence to conclude Russia is committing genocide in Ukraine.

“This a matter of intent, the intent of the criminals, there must be a ‘need’ to destroy a certain group. And such destruction, according to the Genocide Convention, must be physical or biological,” Erik Møse, chair of the U.N. commission, said during a press briefing in Kyiv.

However, the commission has already found evidence of wilful killings, torture, sexual violence, unlawful transfers and deportations committed by Russian troops, the commission said in a statement.

Even though officials find it hard to prove Russian intent behind the killings of civilians, journalists believe that public attention to these crimes can help to bring justice.

“If we keep documenting, if [we] remember, if we keep talking about these crimes, Russians will pay for that,” said Olga Rudenko, the Kyiv Independent c

The course of Russian development over the past decade has explicitly shown that both internal milieu and foreign policy domain have expressed staggering signs of radicalization and growing division between “us” (ethnic Russians) and “them” (non-Russian citizens and foreigners).

The grim irony of contemporary Russia extensively appealing to the legacy of the Great Patriotic War (1941–1945) as a pivotal aspect of Russian identity is that xenophobia, racial hatred and ultra/far right nationalism have by far outgrown the level of street radicals and in one form or another have penetrated various layers of Russian multiethnic and multicultural society. Currently the number of nationalist organizations actively operating in the Russian Federation may have reached 53: 22 of them being ultranationalist and 8 completely prohibited. In addition, according to numerous estimates half of the world far right radicals currently reside on the territory of the Russian Federation. From my prospective, this poses a grave challenge to both Russian society and European peace and security.

Ultranationalist ideology and Russian public consciousness: looking into the past, thinking about the future

Lessons drawn from Russian historical experience have explicitly pointed out one curious tendency: facing a vital necessity of reforms Russian ruling and intellectual elites have usually opted for relying on a fuzzy notion called “conservatism” that served as the main vehicle of anti-reformist, reactionary and anti-democratic forces.

The issues of “conservatism” extensively promoted during the Romanov dynasty reached its apex when the Monarchy encountered with a broad array of challenges brought about by urgent necessity of modernization and reforms that coincided with humiliating defeat in Russian - Japanese war (1904-1905) and the First Russian Revolution (1905). This resulted in growing appeal to “conservatism” emanating from the ruling elites that translated into surging xenophobia, anti-Semitism vividly seen in the “Black Hundreds” movement and ethnic pogroms that had to a certain extent predetermined Russian historical development in the beginning of the twentieth century. As a result, explicit and derogatory discrimination of ethnic minorities pushed members of various ethnic groups onto the road of radicalization and underground revolutionary activities.

That is why today, when Russia is pursuing Eurasian integration and facing proliferation of non-Russian population, historical experience and current level of xenophobia that is acquiring much deeper influence and significantly more sophisticated forms should not be undermined. After all, approximately 53% of Russians are currently supporting the slogan “Russia for Russians!”

Russian far right movement in 1990s – early 2000: menace on the march

Disintegration of the Soviet Union was accompanied by total economic impoverishment of wide layers of Russians, political degradation and raging separatism. On the other front, ideological vacuum that emerged after the demise of the Communism resulted in growing perplexity over the future trajectory of development. The ruling elites at the time were unable/unwilling to clearly formulate national idea – in a country with historically weak civil society, absence of pluralism and clear tilt towards the guidance from above, this was a dramatic and in many respects fateful episode. This ideological void triggered a torrent of ideas and distorted historical narratives that swooped on Russian society. That is why the process of ideological and spiritual renaissance did not acquire forms commensurate with the task of ideological and cultural transformation.

The sense of moral degradation, skyrocketing criminality, growing economic inequality, the bloody Chechen War (1994-1996), the ensued outbreak of terrorism and growing number of migrant workers from the Caucasus and Central Asia facilitated further radicalization of wide masses of Russians engendering emergence of various types of far right and neo-Nazi organizations. On the other hand, the war in Yugoslavia (especially the active involvement of the NATO forces), growing disenchantment with the West that was blamed for dismal economic performance and political failures resurrected anti-Western sentiments within Russian society and promoted the idea of incompatibility between liberal-democratic norms and values and Russian identity with distinct historical mission.

It ought to be mentioned that traditions of far right nationalism in contemporary Russia go back to the times of the Soviet Union, when in the year 1980 “Pamyat” (Memory) was formed from a number of smaller groups (though it was not very numerous and disintegrated in 1985). Ultranationalist/xenophobic movement in Russia in 1990s and the early 2000th did not constitute a homogeneous body and was represented by a patchwork of various forces that varied from underground militarized organizations, open neo-Nazis (skinheads), left wing extremists, Orthodox–Christian nationalists (the “Black Hundreds”; the Russian National Union; the Union of Russian Orthodox People) and national-Imperial (the Communist Party of the Russian Federation; the Liberal Democratic Party; Russian All-People's Union) groups.

In the early 1990s the most visible and well-organized actor among Russian far rights was the Russian National Unity (the RNU). Its militarized underground structure (which may have assembled as many as 100,000 active members in both the Russian Federation and other countries of post-Soviet area) held attributes and symbols similar to the ones used in the Nazi Germany and slogans such as “Glory to Russia!”. Sentiments that defined the conceptual outlook of this group did to a significant extent reflect the pervasive moods and feelings within Russian society: resurging anti-Semitism, explicit anti-Caucasian stance and anti-Americanism.

Another branch, so-called Nazi-skinheads did not have a core organization and was mostly represented by a wide range of incoherent organizations enjoying various extent of popular support. Three main factors contributed to exponential growth of this type of neo-Nazi groups:

-

The First Chechen war (surrounded by aggressive anti-Caucasian information warfare orchestrated by Russian mass media)

-

Economic collapse and plummeting level of education (which resulted in a staggering growth of youth criminality)

-

Distorted understanding of the Second World War

Coupled together these factors created a fertile ground for the most unsophisticated xenophobic ideologies (easily manipulated from above) based on crude violence, ethnic hatred and intolerance. At certain point major Russian cities got submerged under the wave of uncontrollable violence committed by neo-Nazis. Foreigners (especially from countries whose appearance differed from the Slavic one) were afraid of visiting Russia and embassies of countries whose citizens could be targeted on the first place were instructed how to act while being in Russia. Unfortunately, these derogatory actions received tacit support from numerous representatives of Russian political elite. For instance, the Mayor of Moscow Yuri Luzhkov (a notorious nationalist) tried to hush down violent crimes with clear ethnic background. Moreover, in many respects militia and prosecutors as well as certain share of intellectual circles (several noticeable newspapers were not keen to portray skinheads and their crimes in negative light) expressed compassion with actions of violent neo-Nazis. According to numerous estimates by the year 2005 the total number of Nazi-skinheads in Russia may have reached 80,000 members. Victims of neo-Nazi criminals were counted in hundreds – although the accurate number remained unknown because local militia was not interested in classifying crimes as ethnically motivated and great number of migrant workers from Central Asia (who were main target of neo-Nazis) opted for not complaining to the state security services because many of them worked in Russia illegally.

Another force - National Bolshevik Party (NBP) known for its neo-Imperialist, openly xenophobic and anti-liberal activities and ideology represented a peculiar combination of far-right and far-left dogmas. Frequently members of the party have been charged with ethnic crimes, terrorism, seizure of administrative buildings and inducement for separatism in Kazakhstan, Ukraine and the Baltic States. The party had cells and representatives not only in the countries of the post-Soviet area (Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Kazakhstan, Kirgizia and the Baltic States) but also in Israel, Sweden, Canada, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, the UK and Poland. Perhaps, this party should not have been mentioned in scopes of this paper if it was not for Alexandr Dugin (notoriously known neo-Fascist and xenophobe) – one of the most noticeable representatives of contemporary Russian ultranationalism and neo-imperialism who happened to be a founding father of this organization.

In the final analysis, it ought to be mentioned that by the year 2005 xenophobia, racial hatred and ethnic crimes committed by ultranationalists in Russia had become a serious obstacle and a matter of international criticism that the Kremlin (already seeing Russia as an independent pole in international relation) was to somehow mitigate.

In January of 2006, while visiting Auschwitz Vladimir Putin openly acknowledged that anti-Semitism and the skyrocketing of neo-Nazi ideology had constituted a major problem for Russia. Similarly, the Amnesty report, entitled "Russian Federation: Violent racism out of control” explicitly voiced dissatisfaction with race-motivated crimes in Russia.

Taming the dragon or creating Frankenstein? Kremlin and Russian far right nationalism (2005 - 2011)

Visible dangers emanating from uncontrollable violent far right nationalists induced the Kremlin to accept a new tactics that would have marginalized most atrocious groups and promote creation of a layer of “conservative patriots”. On the other hand, increasing antagonism with the US and their European allies (over the invasion of Iraq, expansion of the EU and a parade of “color revolutions”) were exploited by the Kremlin in the process of creation of an imitation of direct participation of masses in political process. In this juncture, nationalist forces were perceived as the most convenient vehicle of communication that could be used both in terms of suppression of opposition and (most importantly) aggressive propaganda campaigns.

This period in development of Russian nationalist movement primarily coincided with emergence in 2003 of “Rodina” (“Motherland”) political project (as a coalition of 30 nationalist and far-right groups that was established by Dmitri Rogozin, Sergey Glazyev, Sergey Baburin and other representatives of nationalist forces), “Nashi” (Ours) youth movement (2005 date of initiation) and breathtaking success of such controversial figures as the already mentioned A. Dugin and Sergey Kurginyan, MikhailLeontiev, Maxim Shevchenko, Nikolai Starikov, Alexandr Prokhanov, Nataliya Narotchnitskaya. The range of ideas represented by this new stronghold of Russian “conservatism” varied from neo-Stalinism to most notorious forms of ethno-nationalism, xenophobia and neo-Fascism.

Nonetheless, ideas promoted by the Kremlin did not yield results tantamount to the expectations. First, “Rodina” party managed to gain much more popularity than it was supposed to. Moreover, youth “patriotic” organizations did not relieve Russian society of raging xenophobic sentiments: on the contrary, starting from the year 2005 Russia experienced an avalanche of ethnic crimes and the rift stipulated by racial discord became even more apparent. More importantly, newly emerged organizations acquired traits of nationalist groupings and started to actively promote ethno-nationalist agendas.

Another clumsy and ill-calculated attempt to “harness” far right movement was the so-called “Russian March” (first celebrated in 2005) – it turned out to be an openly neo-Nazi action initially extensively supported by officials. Incidentally, one of the main organizers of the event was the Eurasian Youth Union (guided by A. Dugin). Later on, this gathering embraced various reactionary elements within Russian society, ranging from neo-Nazis, monarchists, to neo-pagans and Cossacks.

An uneasy alliance: what went wrong?

Very soon however, numerous mistakes in the aforementioned approach became evident. First, imperial nationalism (that was to have acquired predominant positions and pave the way towards re-emergence of the new Russia) was supplemented by growing in popularity ethnic nationalism. Moreover, Nazi-skinhead movement and other military radicals did not cease to exist. International attention was brought to the hideous assassination of Stanislav Markelov (human right activist) and Anastasia Baburova (well-known activist of Russian anti-Nazi movement) that was said to have been committed by the neo-Nazi BORN (literary “Combat Organization of Russian Nationalists”) – this was one of numerous crimes perpetrated by members of this far right group. In addition, in order to boast with significant aggrandizement in the rank-and-file (to attract more financial support) such organizations as “Nashi” tacitly recruited neo-Nazis, skinheads and football hooligans. Most certainly, this jeopardized the Kremlin-inspired project.

What made matters even more complicated was that the role of nationalists in Russia changed dramatically: previously they occupied marginal positions but growing participation in politics made them a convenient ally (in certain respect a tool) of various political forces that tried to manipulate public mass conscious. Such ideas as “Russia for Russians”, “Let us clean Moscow from the garbage”, “Glory to Russia!”, “Say no to migrants from Central Asia”, “Moscow for Muscovites” acquired exponential support. Most perplexing for the Kremlin was that politicians and intellectuals closely associated with ruling elites also abused such slogans and mottoes. Interestingly enough, yet in the year 2013 V. Putin himself explicitly acclaimed the idea of implementation of further restrictions for work migration to Russia – an obvious attempt to use national-populist agendas and gain support from growing nationalist movement. Moreover, in October 2014 during the Valdai Club meeting in Sochi V. Putin openly stated his adherence to nationalism, which he juxtaposed to chauvinist ideology (though conveniently obfuscating the red line between two concepts).2

This picture would be incomplete without pointing out the grave inconsistency and ambiguity in steps taken by the Kremlin. On the one hand, V. Putin and other officials have criticized xenophobia and ethnic intolerance as inadmissible activities for the Russian Federation. Nonetheless, on the other, state sponsored/orchestrated anti-American, anti-Georgian, anti-Ukrainian and anti-Baltic campaigns and a number of popular TV shows (such as “Nasha Russia” –“Our Russia”) that ridiculed population of Central Asia -in particular Tajikistan- clearly suggested that xenophobia and racism emanated from the very top of Russian political architecture. This incoherence and clumsiness raise a logical question: if one sort of xenophobia and racism is to be tolerated and approved, why should its different branches be prohibited?

Putin’s return to office, the war in Ukraine and Russian neo-nationalist dilemma

In the final analysis, it was the decision of V. Putin to return to power that triggered a new lap of frictions within Russian nationalist circles. Certain groups openly opposed this idea. For instance, the so-called “ethnic-nationalists” assumed hostile attitude towards the Kremlin primarily because of alleged discrimination of ethnic Russians as a result of illegal migration and financial support to the North Caucasus. Such organizations as the “Russians Movement”, the “Movement against Illegal Migration”, the “Russian National-Democratic Party”, the “Slavic Alliance” and the “Northern Brotherhood” extensively supported by Slavic neo-pagans, neo-Nazi groupings, explicitly voiced their concern over the trajectory of development of the Russian society.

The most noticeable figure of the neo-nationalism became Alexei Navalny who based his program on criticism of corruption intertwined with “ethnic factors”. Such slogans as “Stop feeding the Caucasus” have enjoyed outstanding rates of popularity especially among young and educated citizens of Moscow – a clear contrast with ill-educated violent have-nots. Moreover, explicit anti-Kremlin stance of A. Navalny and his associates posed a serious problem for aging Russian regime. Worsening economic situation coupled with the dramatic raise of Ramzan Kadyrov underscore not only the fact that the North Caucasus is drifting away from Moscow in each and every sense, yet generates number of serious questions regarding financial means injected in ailing corrupt economies of the region. Indeed, such issues do have powerful effect on many Russians, especially considering that the society has been suffering a malaise called “ethnic division” for a long time and symptoms thereof are likely to progress even further. The issue of populism and crude manipulation with masses based on primitive distortion of facts and ideas currently offered by liberal-nationalists are not new. After all, was it not Vladimir Putin whose breathtaking ascension to power was handsomely saturated with the same ingredients?

The so-called “Russian Spring” was meant to significantly upgrade V. Putin’s plummeting popularity and achieve consolidation of wide layers of Russian society through“rectifying historical injustices” and practical steps aimed at creation of the “Russian World”.Indeed, initially the popular support of V. Putin skyrocketed and visible consolidation of Russian society including nationalist forces seemed to have been achieved. Nevertheless, the “post-Crimea” hangover was starting to fade away with the advent of economic crisis and the outbreak of war in the Southeast of Ukraine. One of the most surprising outcomes for the Kremlin was the actual rift within Russian ultranationalist forces that (primarily due to the lack of knowledge and mostly distorted information provided by Russian mass media) started to perceive the ongoing conflict from two diverging prospective. Naturally, the larger part of Russian nationalist forces fully supported pro-Russian rebels in Donbass, whereas certain layers were in favor of Euromaidan because of its alleged tilt towards ethnic nationalism (in this juncture, the “Azov” battalion was hailed as a force representing genuine ideas of Slavic ethno-nationalism). The most evident corroboration of this tendency was the fact that in 2014 Russian nationalists took part in three different sections of “Russian March” (ideologically adverse to each other) and with visible ideological countercharges expressed by all sides.

Perhaps, another matter of deep concern lies within the following: it is not a secret that Russian far right nationalists are fighting on both sides of the front line. In case the conflict subsides, many militants are likely to return home. The impact of their “re-integration” into the peaceful life could yield unpredictable results. After all, experience of the two Chechen wars clearly showed that many solders could not easily return back to normal. On the other hand, it would be safe to suggest that the “heroes” of the war in Ukrainian Southeast, such as Igor Strelkov (Girkin), have accumulated visible support within radical circles – especially those who accuse the Kremlin of inability/unwillingness to conduct coherent policy in respect to the “Novorossiya” and Russian speaking minority in Ukraine. Strelkov might appear as a new phenomenon within Russian nationalist milieu – his outlook consists of a combination of Imperial–Orthodox line and inevitability of re-emergence of the new Russia under the dictatorship of a Stalinist/Tsarist model. For this type of nationalists Vladimir Putin is seen as weak and indecisive leader and the political opposition is perceived as national traitors to be done away most decisively. These nationalists are not populists interested in accretion of wealth – they are idealist with fanatic creed in their historic mission. This could be extremely dangerous combination given Russian (and European) historical experience of the first half of the 20th century.

Generation 3.0: far right ideology in the changing Russia

In order to understand the role of nationalist ideology in post-2012 Russia, one need to take closer look at both internal and external factors that have played crucial role in transformation of the Kremlin’s goals and strategies related to this phenomena. Aggressive perception of the “outer world” reflected in the “spheres-of-influence” approach and explicit anti-West sentiments have contributed to the changing role of xenophobic and ultranationalist groups and organization in the Russian Federation. In this regard, two key dates should be discerned: the year 2007 (notorious Munich conference) and 2008 (the war between Russia and Georgia). Starting from these two events that shook the essence of European and post-Soviet countries European ultranationalists have been providing support for Russian foreign policy actions aimed at re-integration of former Soviet republics into the Kremlin’s sphere of influence. For many radicals in Europe Russia and Vladimir Putin appear to be the only remaining custodian of conservatism, Christian values and self-sufficient foreign policy. Moreover, given the great role of anti-Americanism (and anti-NATO moods) in Europe, radical forces admire V. Putin for being able to openly challenge the unipolar post-Cold War world dominated by the US. In addition, allegedly tough subordination of Chechnya (though the image promoted by mass media does not reflect the real state of affairs) by the means of decisive military measures provides an erroneous image of Russia in Europe. Acting in scopes of “divide and rule” tactics the Kremlin has been willing to engage in close relations with European far rights using Russian nationalist organizations and individuals for establishing and maintaining close contacts. These ties have been secured by personal active contribution of the Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin (one of the founding fathers of “Rodina”), Anatoly Zhuravlev (representative of the United Russia), A. Dugin and other notorious Russian nationalists who have been able to establish cordial relations with and attain broad understanding and support from the European far rights. Clearly such relations have been coordinated and guided from the very top of the existing power architecture in the Russian Federation. International mass media have also unraveled extensive evidences3 of significant financial support the Kremlin is ready to provide for major European far right organizations. Moreover, the dialogue with European far rights is particularly vital for the Kremlin in countries strategically important from energy security point of view – this is easily deducible from the map of Russian oil/gas pipelines stretching to the EU and the state of relations between the local and Russian far rights.

It appears however, that the strong desire to derive support from the side of European nationalists may have resulted in a number of miscalculations. For instance, the first International Russian Conservative Forum that took place in Saint Petersburg on March 22 2015 attracted open neo-Nazis and criminals – to the extent that even Marine Le Pen (a well-known admirer of V. Putin) turned down the invitation in order not to be involved in such a derogatory assembly. The event was also severely criticized by the majority of Russian liberals and anti-fascists, whereas the Kremlin opted to dissociate itself from the event.

From the other prospective, the Kremlin does not shy away from using the scary image of Russian violent Nazi-skinheads and radicals responsible for crimes and ethnic pogroms (such as in Kondopoga and Birylevo) hinting that the current elites are by far more civil and predictable than other far right nationalist forces and that the potential raise to power of far more ultranationalist forces could bring about irreparable damage not only to the Russian Federation itself yet for the entire continental security architecture. In the final analysis, Russian historical experience of the first quarter of the 20th century might be seen as an argument compelling enough for the European elites to continue cooperation with current political regime.

On the domestic front, the Kremlin has inspired a new project called “Antimaidan”whose purpose is “to prevent ‘color revolutions’ in Russia”. It assembles a broad array of forces under the banners of “conservatism”, “patriotism” and “inadmissibility of Maidan in Russia”. Incidentally, leader of this group include not only well-known intellectuals and civil activists with far going connections with the Kremlin (such as Nikolai Starikov and Dmitry Sablin), but also the leader of the Russian motorcycle club-gang “the Night Wolves”, Alexander “the Surgeon” Zaldostanov, who enjoys personal friendship with the Russian President V. Putin.

In certain respect, it might appear as a reiteration of moves previously conducted by the Kremlin, although there are crucial differences that need to be taken into account. The composition of this project drastically differs from the previous ones: youth, sportsmen, intellectuals, Cossacks, military veterans and nationalists have been merged together into an organism that will be able to act in broad scopes and without any remorse. The main justification of any actions (as though and derogatory as they might be) will be the fuzzy concept of “public good”. Many experts have already come up with a historical similarity between the “Antimaidan” and German SA paramilitary forces or the infamous “death squads” in Latin America and even the Red Guards in China.

The question however appears to be much more sophisticated and perilous than it seems on the surface. By now it remains unclear if this new project signifies yet another attempt to use nationalist forces for specific goals or whether this move is an inception of a new chapter of Russian history with a long lasting tradition of authoritarianism and repressions against opposition.

We infiltrate the Russian Neo-Nazi group “Autonomous Nationalists”, one of most brutal right-wing, extremist groups in the world. Shocking footage shows them attacking foreigners, setting fire to buildings and training to use knives. Even more worrying are the ties between Autonomous Nationalists and other extremist groups in Germany and Europe. One member describes how they would regularly train with Neo-Nazis from Europe. “There was a real program with target practice . We showed the Europeans how to use our weapons most effectively and exchanged experiences” In candid interviews, members are quick to praise the Third Reich. “I support the theory of the supremacy of the white race and the superiority of the Russian people” states Dimitry. Another describes how he attacks foreigners, who he blames for spreading ’drugs and death’. And it’s not only men attracted to this dangerous ideology. At the training camp, we film some of the women attending and learn how they were recruited. We also see how the neo-Nazis use seemingly harmless web pages and youth affine topics to spread their radical views.

Who Are The Neo-Nazis Fighting For Russia In Ukraine?

The video, published in December 2020, showed two nattily dressed Russian men -- waistcoats, pocket squares, silk ties – sipping American whiskey in brandy snifters and discussing killing Ukrainians.

"I'm a Nazi. I’m a Nazi,” said one of the men, Aleksei Milchakov, who was the main focus of the video published on a Russian nationalist YouTube channel. “I'm not going to go deep and say, I’m a nationalist, a patriot, an imperialist, and so forth. I’ll say it outright: I’m a Nazi.”

“You have to understand that when you kill a person, you feel the excitement of the hunt. If you’ve never been hunting, you should try it. It’s interesting,” he said.

Aside from being a notorious, avowed Nazi known for killing a puppy and posting bragging photographs about it on social media, Milchakov is the head of a Russian paramilitary group known as Rusich, which openly embraces Nazi symbolism and radical racist ideologies. The group, and Milchakov himself, have been credibly linked to atrocities in Ukraine and in Syria.

Along with members of the Russian Imperial Movement, a white supremacist group that was designated a "global terrorist" organization by the United States two years ago, Rusich is one of several right-wing groups that are actively fighting in Ukraine, in conjunction with Russia’s regular armed forces or allied separatist units.

According to a confidential report by Germany’s Federal Intelligence Service, which was obtained by Der Spiegel and excerpted on May 22, numerous Russian right-wing extremists and neo-Nazis are fighting in Ukraine.

German analysts wrote that the fact that Russian military and political leaders have welcomed neo-Nazi groups undermines the claim by Putin and his government that one of the principal motives behind the invasion is the desire to “de-Nazify” Ukraine, Spiegel said.

This fact, Spiegel quoted the report as saying, renders "the alleged reason for the war, the so-called de-Nazification of Ukraine, absurd.”

From Syria to Ukraine

Even before the February 24 invasion, the war in Ukraine had drawn a substantial but unknown number of soldiers and fighters with right-wing sympathies. Most of the attention has long focused on right-wing militias and paramilitaries that have fought alongside or as part of Ukraine’s armed forces -- a phenomenon dating back to the start of the conflict in the Donbas in 2014.

Ukraine’s famed Azov Regiment was formed out of a right-wing militia called the Azov Battalion that gained renown in the early days of the war. The group’s leaders and founders openly espoused xenophobic and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Its logos bore a close resemblance to some used by Nazi units during World War II.

Later incorporated into Ukraine’s National Guard, Azov has toned down in extremist rhetoric, but retained a reputation as a formidable fighting unit.

For years, Russian officials have seized on Azov as well as 20th century nationalist figures like Stepan Bandera and others for propaganda purposes, often distorting or exaggerating their views and actions in support of the false assertion that Ukraine is controlled or dominated by neo-Nazis.

In announcing the invasion on February 24, Putin attempted to justify it by saying the goals were “demilitarization and de-Nazification.” Kyiv and Western governments say that argument is disingenuous and say, even if it was true, it wouldn’t justify launching an unprovoked invasion against a country with a democratically elected government.

Less attention, however, has been paid over the years to right-wing Russian militias fighting on behalf of Russia, not just in Ukraine but also in Syria.

While some fighters are believed to have joined the ranks of Russian private mercenary companies -- Vagner is the best known -- an unknown number of fighters joined, and trained under, Rusich, as well as the Russian Imperial Movement and its paramilitary unit, the Russian Imperial Legion.

Milchakov, a former paratrooper, has been identified by experts as the co-leader of Rusich, along with another Russian named Yan Petrovsky. Some experts say the group is explicitly affiliated with Vagner.

The Rusich group was formally founded as the Sabotage and Assault Reconnaissance Group Rusich in St. Petersburg in 2014.

Both Milchakov and Petrovsky fought against Ukraine as volunteers in the Donbas in 2014 and 2015 and have openly displayed patches awarded to them as part of the "Union of Donbas Volunteers.” At the time, however, Russia repeatedly denied its forces were fighting in the Donbas, asserting, while often straining credulity, that the local forces battling Ukrainian troops were merely local partisans.

In September 2014, near the Luhansk Oblast village of Shchastya, Rusich militants battled a Ukrainian paramilitary group called Aidar. Ukrainian news reports said dozens of Ukrainian soldiers were killed. Afterward, images of mutilated and burnt bodies circulated online, and Milchakov later openly bragged about photographing the bodies.

Milchakov also gained notoriety that same year when bloggers and reporters discovered a series of photos and videos from two years earlier in which he was shown killing a puppy, cutting off its head and allegedly eating it.

The tabloid Russian newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets titled an article about the gory incident “A Fascist Butcher From St. Petersburg Has Gone To Fight For The Insurgents.”

In early 2015, Milchakov and Petrovsky were sanctioned by Canada, Britain, and the European Union. Milchakov “has actively supported actions and policies which undermine the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine and to further destabilize Ukraine,” Britain said in its sanctions announcement.

In October 2016, Petrovsky was arrested in Norway, where he had been living and working alongside a Norwegian man tied to the right-wing group Soldiers of Odin. He was deported that same month.

Photographs and videos posted to social media in 2020-2021 indicated that Rusich fighters were in Syria, where Russia has conducted a military operation to back the Syrian regime and eliminate opposition fighters there. The St. Petersburg media outlet Fontanka in late 2017 also found photographs of Milchakov swimming in a pool near Palmyra.

The German intelligence report said Rusich fighters have been in Ukraine since early April.

There’s no confirmation that Milchakov or Petrovsky are or have been in Ukraine at any time since the February 24 invasion. However, on May 27, a Telegram channel that appeared to be affiliated with Rusich published an undated photograph that purported to show both Milchakov and Petrovsky in Ukraine, standing in front of a semi-destroyed armored vehicle.

Milchakov…is back in action,” the post said. “Now he is somewhere in the vastness of Ukraine actively engaged in de-Nazification and demilitarization.”

'Reserve Squad'

The day that Russia launched its invasion, the head of the Russian Imperial Movement, Denis Gariyev, posted a message on his Telegram channel saying: "Without a doubt, we are in favor of the liquidation of the separatist entity Ukraine.”

Founded in 2002 in St. Petersburg by Stanislav Vorobyov, the Russian Imperial Movement subscribes to a monarchist ideology, partly derived from a belief that Russia should be led by a descendent of the Romanov dynasty, the family of the last Russian tsar.

In April 2020, the U.S. State Department imposed sanctions on the group, as well as Vorobyov, Gariyev and another man.

The group “has provided paramilitary-style training to white supremacists and neo-Nazis in Europe and actively works to rally these types of groups into a common front against their perceived enemies,” the department said in a statement. The movement “has two training facilities in St. Petersburg, which are likely being used for woodland and urban assault, tactical weapons, and hand-to-hand combat training.

A few weeks after Gariyev’s Telegram post, the organization's combat training center in near St. Petersburg, called Partizan, announced the recruitment of volunteers to fight in Ukraine.

Gariyev has also created a related organization called Reserve Squad, which, according to the German intelligence report, has received multimillion-dollar orders from the Interior Ministry, the Federal Security Service, and the Federal Protective Service, which is the government agency charged with providing bodyguard protection to top Kremlin officials.

Like with Rusich, fighters with the Russian Imperial Legion joined the hostilities in eastern Ukraine in 2014-2015, and according to information provided by the militants, at least six members of the group were killed then.

According to German intelligence, Gariyev was wounded in fighting in mid-April, and his deputy, Denis Nekrasov, was killed, possibly near the Kharkiv Oblast city of Izyum.

Aleksandr Verkhovsky, a longtime expert on extremist groups in Russia and head of the research center SOVA, said that there were likely far fewer Russian extremist fighters in Ukraine now than there were in the early years of the Donbas war.

“Nationalists played a key role in the first phase of the war,” he told Current Time. “They were a significant part, not a majority, but significant. Now we don’t see here a large number of volunteers from Russia…. Maybe a maximum of a few dozen.”

Decrying Nazism – even when it’s not there – has been Russia’s ‘Invade country for free’ card Published: July 14, 2022 2.32pm CEST

Oleg Morozov, a member of the Russian parliament and an ally of President Vladimir Putin’s, made what sounded much like a threat in May 2022.

Poland should be “in first place in the queue for denazification after Ukraine,” he said.

Just days earlier, pro-Putin Moscow city assembly member, Sergey Savostyanov, asserted that after Ukraine, Russia needs to drive alleged Nazis from power in six more countries: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Moldova and Kazakhstan.

Just a few months following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which was made under the false pretense of denazifying the government of that country, such claims might send chills down the spines of the people in those countries as well as of many keen observers of the region.

It could be argued that such claims of denazification “might be dismissed as the hyperbolic expression of one individual in the overheated atmosphere of Russia today,” as scholar and former diplomat Paul Goble recently described it. Yet it’s evident that for over a decade, Russia has used lies and disinformation, including many references to denazifiying Ukraine, to build a case specifically for the Ukraine invasion.

And unsupported claims of denazification have been an excuse for Russian international aggression since World War II.

Putin and his allies have attempted to expand the meaning of “Nazism” to essentially render it meaningless – but still useful to them. Anyone who opposes Putin’s government can be labeled a Nazi, representing basically the worst and most horrible enemies Russia has ever faced in its history, the battle against whom cost almost 1 in 6 Soviet lives, civilian and military.

The opposition is fascist As a scholar of Russian diplomatic communication, I have researched Russian use of language to justify its military interventions. I found that Russian diplomats inconsistently use and misuse international law expressions to justify Russian actions aimed at gaining either more influence or territory.

And the label “Nazi” has been selectively used and misused to target the perceived opponents of the Putin regime, at times with some success. Indeed, on one extreme, according to Putin’s propogandists, Nazism doesn’t even have to be antisemitic. To Russian officials, anyone who expresses anti-Russian sentiment can be denounced as a Nazi. That allowed Russia to claim that Ukraine was run by Nazis, even though President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is Jewish.

In May 2022, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, a strong ally of Putin’s, accused the West of supporting Nazi ideas. Also in May, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs articulated that the Israeli government is supporting neo-Nazis in Ukraine. This assertion came right after Israel demanded an apology for Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s claim that Hitler had Jewish origins.

Long-running accusations Nowhere has Russia been more persistent with accusations of Nazism than in Estonia and Latvia, two countries with sizable Russian-speaking populations and membership in the European Union and NATO.

For decades, Russia has alleged that fascist ideas have been circulating in these countries on a large scale and have become mainstream. In 2007, Putin said that he is dismayed by Estonia and Latvia’s alleged reverence for Nazism: “The activities of the Latvian and Estonian authorities openly connive at the glorification of Nazis and their accomplices. But these facts remain unnoticed by the European Union.”

In 2012, Russia reacted angrily to a recent gathering of World War II veterans in Estonia and stated that it was aimed at “glorification of former SS-men and local collaborationists.”

In 2022, Latvia designated May 9 as the Day of Remembrance for those killed in Ukraine as a result of the Russian invasion. This move was sure to irk some folks in Russia, as Russia celebrates the Soviet victory over the Nazis in World War II on the very same day. Latvia was at the time also debating the removal of monuments to Soviet-era soldiers.

In response, Putin’s spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said that “the ruling regime in Latvia has long been well known for its neo-Nazi preferences.”

The pot calling the kettle Meanwhile, another debate rages about whether Russia under Putin itself can be seen as a fascist state. On one hand, Putin’s dictatorship has embraced expansionist militarism, crushed domestic opposition, promoted toxic nationalism and revived Russian patriotism by building national identity around the Russian defeat of Nazi Germany.

On the other hand, those who argue that Russia may be a repressive and aggressive dictatorship – but not a fascist state – note that fascism is a fundamentally revolutionary ideology and tends to be accompanied with mass mobilization. Meanwhile, Putin is viewed by many as a reactionary right-wing dictator who is not guided by revolutionary ideas, does not have much charisma and is governing a largely passive population. His supporters will likely continue labeling perceived adversaries as Nazis. Such rhetorical groundwork could eventually lead to more wars beyond Ukraine.

How the Russian Media Spread False Claims About Ukrainian Nazis By Charlie SmartJuly 2, 2022

In the months since President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia called the invasion of Ukraine a “denazification” mission, the lie that the government and culture of Ukraine are filled with dangerous “Nazis” has become a central theme of Kremlin propaganda about the war.

Russian articles about Ukraine that mention Nazism

A data set of nearly eight million articles about Ukraine collected from more than 8,000 Russian websites since 2014 shows that references to Nazism were relatively flat for eight years and then spiked to unprecedented levels on Feb. 24, the day Russia invaded Ukraine. They have remained high ever since.

The data, provided by Semantic Visions, a defense analytics company, includes major Russian state media outlets in addition to thousands of smaller Russian websites and blogs. It gives a view of Russia’s attempts to justify its attack on Ukraine and maintain domestic support for the ongoing war by falsely portraying Ukraine as being overrun by far-right extremists.

News stories have falsely claimed that Ukrainian Nazis are using noncombatants as human shields, killing Ukrainian civilians and planning a genocide of Russians.

The strategy was most likely intended to justify what the Kremlin hoped would be a quick ouster of the Ukrainian government, said Larissa Doroshenko, a researcher at Northeastern University who studies disinformation. “It would help to explain why they’re establishing this new country in a sense,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “Because the previous government were Nazis, therefore they had to be replaced.”

Multiple experts on the region said the claim that Ukraine is corrupted by Nazis is false. President Volodymyr Zelensky, who received 73 percent of the vote when he was elected in 2019, is Jewish, and all far-right parties combined received only about 2 percent of parliamentary votes in 2019 — short of the 5 percent threshold for representation.

“We tolerate in most Western democracies significantly higher rates of far-right extremism,” said Monika Richter, head of research and analysis at Semantic Visions and a fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.

The common Russian understanding of Nazism hinges on the notion of Nazi Germany as the antithesis of the Soviet Union rather than on the persecution of Jews specifically said Jeffrey Veidlinger, a professor of history and Judaic studies at the University of Michigan. “That’s why they can call a state that has a Jewish president a Nazi state and it doesn’t seem all that discordant to them,” he said.

Despite the lack of evidence that Ukraine is dominated by Nazis, the idea has taken off among many Russians. The false claims about Ukraine may have started on state media but smaller news sites have gone on to amplify the messages.

Social media data provided by Zignal Labs shows a spike in references to Nazism in Russian language tweets that matches the uptick in Russian news media. “You see it on Russian chat groups and in comments Russians are making in newspaper articles,” said Dr. Veidlinger. “I think many Russians actually believe this is a war against Nazism.”

He noted that the success of this propaganda campaign has deep roots in Russian history. “The war against Nazism is really the defining moment of the 20th century for Russia,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “What they’re doing now is in a way a continuation of this great moment of national unity from World War II. Putin is trying to rile up the population in favor of the war.”

Mr. Putin alluded to that history in a speech on May 9 for the Russian holiday commemorating victory over Nazi Germany. “You are fighting for our motherland so that nobody forgets the lessons of World War II,” he said to a parade of thousands of Russian soldiers. “So that there is no place in the world for torturers, death squads and Nazis.”

A key feature of Russian propaganda is its repetitiveness, Ms. Richter said. “You just see a constant regurgitation and repackaging of the same stuff over and over again.” In this case, that means repeating unfounded allegations about Nazism. Since the invasion, 10 to 20 percent of articles about Ukraine have mentioned Nazism, according to the Semantic Visions data.

Experts say linking Ukraine with Nazism can prevent cognitive dissonance among Russians when news about the war in places like Bucha seeps through. “It helps them justify these atrocities,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “It helps to create this dichotomy of black and white — Nazis are bad, we are good, so we have the moral right.”

The tactic appears to work. Russians’ access to news sources not tied to the Kremlin has been curtailed since the government silenced most independent media outlets after the invasion. During the war, Russian citizens have echoed claims about Nazism in interviews, and in a poll published in May by the Levada Center, an independent Russian pollster, 74 percent expressed support for the war.

Part of what makes accusations of Nazism so useful to Russian propagandists is that Ukraine’s past is entangled with Nazi Germany.

“There is a history of Ukrainian collaboration with the Nazis, and Putin is trying to build upon that history,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “During the Second World War there were parties in Ukraine that sought to collaborate with the Germans, particularly against the Soviets.”

Experts said this history makes it easy for the Russian media to draw connections between real Nazis and modern far-right groups to give the impression that the contemporary groups are larger and more influential than they are.

The Azov Battalion, a regiment of the Ukrainian Army with roots in ultranationalist political groups, has been used by the Russian media since 2014 as an example of far-right support in Ukraine. Analysts said the Russian media’s portrayal of the group exaggerates the extent to which its members hold neo-Nazi views.

Russian television regularly featured segments on the battalion in April when members of the group defended a steel plant in the besieged city of Mariupol.

“For Russia, it was a perfect opportunity,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “It was like, ‘We’ve been smearing them for so long and they’re still there, they’re still fighting, so we can justify our tactics of destroying Mariupol because we need to destroy these Nazis.’”

Russia’s false claim that its invasion of Ukraine is an attempt to “denazify” the country has been criticized by the Anti-Defamation League, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and dozens of scholars of Nazism, among others.

“The current Ukrainian state is not a Nazi state by any stretch of the imaginiation,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “I would argue that what Putin is actually afraid of is the spread of democracy and pluralism from Ukraine to Russia. But he knows that the accusation of Nazism is going to unite his population.”

Published: 03.04.2022 Antisemitism Globally March 04, 2022

“When Ukrainian nationalists and Jews look at those red and black flags, we see two different things.” – Prof. David Fishman

By Andrew Srulevitch, ADL Director of European Affairs

As the Russian assault on Ukraine has intensified, the Russian president and his government has escalated rhetoric falsely labeling the Ukrainian government and its leaders as “Nazis.” President Vladimir Putin has claimed that the military action is aimed at the “denazification of Ukraine” and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov called the Ukrainian president “a Nazi and a neo Nazi.”

Earlier this week, I spoke to Dr. David Fishman, a professor of Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary, about how Russian propaganda, including rhetoric linking Ukraine and the Nazis, is being used as part of a campaign of disinformation in an attempt to discredit the democratically elected Ukrainian government.

Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Q: Why does Putin think it makes any sense to call Ukrainian leaders Nazis, especially when President Zelensky is Jewish?

Dr. Fishman: “This propaganda is an attempt to delegitimize Ukraine in the eyes of the Russian public, which considers its war against Nazi Germany its greatest moment, and in eyes of the Western publics who may not know much about Ukraine except that it’s next to Russia.”

Q: But why call them Nazis, aside from that being the worst accusation one can make?

“This propaganda isn’t new. Russia has for years highlighted the activity of a marginal group of Ukrainian ultra-nationalists as a way of trying to stigmatize all of Ukraine. Yes, some members of these ultra-nationalist groups have used Nazi insignia, made Hitler salutes, and used antisemitic rhetoric, but they are politically insignificant and in no way representative of Ukraine. The political parties which the ultra-nationalists support received just over 2 percent of the vote in the 2019 elections. Ukraine is a flawed democracy, but unquestionably a democracy, and in no way a Nazi regime.”

Q: But we’ve seen torchlit marches in the middle of Kyiv with the red and black flags of UPA (the WWII-era Ukrainian Insurgent Army) and pictures of Stepan Bandera, who allied with the Nazis during WWII. Isn’t that evidence of Nazism in Ukraine?

“For Ukrainian nationalists, UPA and Bandera are symbols of the Ukrainian fight for Ukrainian independence. The UPA allied with Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union for tactical – not ideological – reasons. For Jews, however, not only is allying with the Nazis unforgivable under any circumstance, but historians have documented that Ukrainian nationalists participated together with Germans in the murder of many thousands of Jews in Ukraine.

“We should also not forget that 10 million Ukrainians fought in the Red Army against Nazi Germany and 1.5 million Ukrainians died in combat. The number of Ukrainians who fought the Nazis dwarfs the number who collaborated with them. When Ukrainian nationalists and Jews look at those red and black flags, we see two different things.”

Q: So you wouldn’t term as Nazis even those who march with the red and black flag?

“There are neo-Nazis in Ukraine, just as there are in the U.S., and in Russia for that matter. But they are a very marginal group with no political influence and who don’t attack Jews or Jewish institutions in Ukraine. Putin’s propaganda is so far from the truth that it doesn’t survive the first contact with even a little knowledge.”

Is there any truth to Russia's 'Ukrainian Nazis' propaganda? Kathrin Wesolowski 12/03/2022December 3, 2022 Russian propagandists are constantly saying Ukraine is full of Nazis, and posting alleged evidence online. DW's fact-checking team has investigated some of this supposed evidence.

Ever since the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and even before, there were stories circulating that claimed many Ukrainians were adherents of Nazism. On well-known propaganda channels such as the German-language Telegram group "Neues aus Russland" ("News from Russia"), run by the allegedly independent journalist Alina Lipp, assertions regarding "Ukrainian Nazis" are rife. Such posts are influential — Lipp's channel alone has more than 183,000 subscribers.

A simple search on the channel shows that the word "Nazi" occurs 285 times, "National Socialism" 22 times and "swastika" 17 times (as of November 25).

But why is there this narrative about Ukrainian Nazis? And what about the alleged evidence spread by pro-Russian accounts on social media?

Claim No. 1: A video in a tweet allegedly coming from the Arab news broadcaster Al Jazeera says three drunk Ukrainians spread Nazi symbols at the football World Cup in Qatar.

DW fact check: False